Trade Tensions Ignite Global Market Shake-Up

US-China investment trends are undergoing a seismic shift as an escalating trade war and tech rivalry disrupt the status quo. Investors worldwide are closely watching these developments: a clash of tariffs, volatile markets, and the rise of emerging economies are creating new winners and losers. In this report, we break down the key developments, analyze the political and economic impacts on both the United States and China, and explore what the future might hold for global markets.

The Trump tariff impact has been felt across industries from agriculture to technology, sending ripples through stock exchanges in New York and Shanghai. High-profile investors like Ray Dalio, David Tepper, and Ruchir Sharma offer strikingly different perspectives – from warnings of historical parallels to strategies for profit amidst turmoil. Meanwhile, the BRICS nations are charting their own course, with China and its partners challenging U.S. dominance by leveraging their growing economic clout. In the following sections, we provide a balanced, fact-driven analysis of these trends, backed by market data and expert insights.

Quick Insights

- Tariffs Upend Trade Flows: The U.S.-China trade war saw aggressive tariffs on hundreds of billions in goods, reshaping supply chains and pushing China to seek new suppliers (e.g. Brazil for soybeans).

- Market Winners & Losers: U.S. steel producers boomed under protection (prices +1.5%, added ~4,800 jobs) while manufacturers and farmers took a hit (manufacturing index fell to 10-year low; soybean exports plunged, costing U.S. farmers $11 billion). Chinese tech companies like Alibaba and JD.com saw mixed fortunes – facing crackdowns at home yet attracting foreign investment as valuations dipped.

- Investor Sentiment Splits: Billionaires diverge on strategies. Ray Dalio notes rising conflict risks and U.S. debt woes, David Tepper trimmed U.S. stocks amid tariff fears but later bet big on Chinese tech stocks (boosting Alibaba and JD.com holdings), while Ruchir Sharma warns U.S. market dominance may be a “mother of all bubbles”.

- BRICS vs. U.S. Trajectories: The BRICS economies (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) now make up ~35% of global GDP vs the G7’s 30%, a stunning shift from 1990s when the U.S.-led G7 towered over emerging markets. China’s growth slowed to a ~30-year low of 6.1% in 2019 amid the trade war, but remains robust relative to Western peers, and India is emerging as a new growth engine.

- Opportunities & Risks Ahead: Chinese tech stocks rally on innovation in AI and government stimulus, even as U.S. export bans (e.g. on chips) loom. The U.S. economy enjoys a strong run with record stock highs, but faces headwinds from high debt and inflation. Investors are eyeing alternative markets and assets (from commodities to emerging market equities) to hedge against geopolitical uncertainty.

Key Developments in the US-China Economic Rift

The economic dance between the U.S. and China has entered a volatile new phase. In early 2018, President Trump launched a barrage of tariffs on Chinese imports, aiming to pressure Beijing over trade imbalances and intellectual property theft. China retaliated in kind, and a tit-for-tat trade war ensued. Markets reacted swiftly: major U.S. stock indices see-sawed with each new tariff announcement or negotiation rumor, while China’s Shanghai Composite slumped into a bear market during the height of tensions. By late 2019, trade uncertainty was sapping business confidence – U.S. manufacturing activity tumbled to its lowest level since 2009, and global growth projections were revised downward.

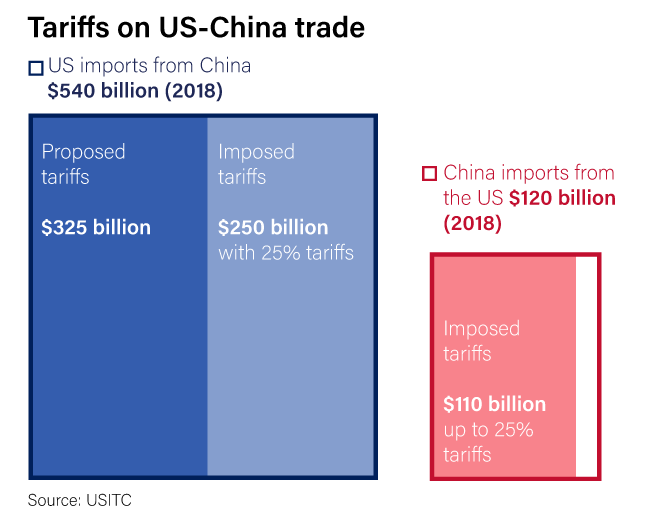

Tariffs imposed in the U.S.-China trade war (2018–2019). The U.S. levied 25% duties on $250 billion worth of Chinese imports (blue) and threatened additional tariffs on a further $325 billion, while China retaliated with tariffs on about $110 billion of U.S. goods (red). This disparity underscores how much larger U.S. imports from China were, giving Washington more targets for tariffs than Beijing

Tensions peaked in May 2019 when Washington not only hiked tariffs on $200 billion of Chinese goods to 25%, but also blacklisted tech giant Huawei – a move that hit at the heart of China’s tech ambitions. Beijing answered with its own tariff increases on $60 billion of U.S. products and warned of export controls on critical minerals. Each escalation rattled investors: Chinese tech stocks plunged on news of U.S. sanctions, while shares of U.S. companies with heavy China exposure (from chipmakers to farmers’ equipment manufacturers) also sold off. Yet, there were also rallies on optimism whenever talks appeared to make progress – for instance, global markets breathed a sigh of relief after the late 2019 “Phase One” trade deal framework eased the conflict.

Amid this turbulence, influential investors adapted their strategies. Billionaire David Tepper initially sounded alarms that trade tensions could slash equity values by 5–20% and disclosed he had cut his U.S. stock exposure by about 30%. “Markets are fairly valued if you don’t have tariffs on China… If you do, you have to be cautious,” Tepper noted. However, by 2024, as Chinese equities hit multi-year lows, Tepper saw an opening: he poured funds into Chinese e-commerce and internet stocks like Alibaba (his fund’s largest holding) and JD.com, boosting positions even as others fled the sector. His contrarian bet came just in time for a rebound – helped by China’s surprise advances in artificial intelligence and renewed policy support, which sent the Hang Seng Tech Index up over 20% (entering bull market territory)

Not all moves were bullish on China. Many U.S. investors, wary of Beijing’s regulatory crackdowns and slowing growth, rotated money back to Wall Street. This homeward shift contributed to U.S. equities swelling to unprecedented global dominance. By late 2024, U.S. stocks accounted for about 70% of the MSCI World Index (which tracks global equities) – more than double their share in the 1980s. Veteran emerging-markets strategist Ruchir Sharma cautioned that investors’ “awe of ‘American exceptionalism’ in markets has now gone too far”. In his view, the U.S. stock surge – supercharged by tax cuts, tech sector profits, and global capital flight to safety – risked becoming “the mother of all bubbles” if fundamentals don’t catch up.

Through 2020 and beyond, the key developments have been characterized by this push-and-pull: trade policy shocks on one hand, and investor repositioning on the other. While the trade war has moderated since the Phase One truce (tariffs largely remain but stopped growing), the rivalry simply shifted arenas – into technology (export controls, supply chain decoupling) and capital markets (scrutiny of Chinese firms listing abroad, restrictions on investment flows). Each development set the stage for significant political and economic fallout in both countries.

Political and Economic Impacts on the U.S. and China

The repercussions of the U.S.-China economic rift have been profound and often paradoxical. In the United States, tariffs ostensibly aimed at protecting industries had mixed results. For example, American steelmakers enjoyed a brief renaissance after 25% steel import duties were imposed in 2018 – domestic steel prices jumped, production rose 1.5%, and roughly 4,800 steel jobs were added by 2019. Capacity utilization at U.S. mills climbed above 80% for the first time in years. However, these gains came at a steep cost to downstream manufacturers. Companies that rely on steel for inputs (from auto makers to construction equipment firms) faced higher raw material costs, forcing some to lay off workers. Economists estimate about 80 jobs in steel-using sectors were put at risk for every steel job saved by tariffs. The broader manufacturing sector slipped into contraction – by late 2019 the U.S. PMI index was signaling the first manufacturing recession since the Great Recession, a slump largely attributed to the trade war dampening exports and capital spending. In short, Trump’s tariff impact was a double-edged sword: bolstering certain industries while unintentionally hurting others.

Agriculture was another arena of collateral damage. China’s retaliatory tariffs targeted heartland exports like soybeans, corn, and pork. U.S. soybean sales to China, previously a ~$12 billion-a-year trade, plummeted. Beijing turned to alternate suppliers, and Brazil emerged as the big winner. By 2018, Brazil was supplying over 80% of China’s soybean imports, up from about 50% a few years prior. U.S. farmers, meanwhile, saw soybean exports fall so sharply that one estimate pegged the loss at $11 billion in lost sales during the trade war’s peak. The U.S. government issued billions in farm bailout payments to offset the pain. This shift not only strained the rural economy but also realigned global trade patterns in commodities.

Regional Spotlight: Brazil’s Agricultural Windfall

Brazil’s economy, part of the BRICS, experienced a regional boost amid the U.S.-China spat. As China slapped tariffs on American soybeans, Brazilian farmers seized the opportunity. Soybean exports from Brazil to China surged to record levels, filling the gap and earning Brazil substantial export revenue. Investment flowed into Brazil’s agribusiness sector – from expanding port facilities to forging new trade deals – to solidify its role as China’s top soy supplier. This windfall was a much-needed bright spot for Brazil, which had been struggling with recession earlier in the decade. However, it also underscored Brazil’s growing dependence on Chinese demand. By catering more to China, Brazil benefited in the short term, but became more exposed to any slowdown in China or shifts in Chinese import policy. This example highlights how one BRICS nation capitalized on superpower tensions, illustrating the complex ripple effects of the US-China trade war on third countries.

In China, the trade war and investment pullback have likewise been a story of resilience amid challenges. Export industries and manufacturing hubs in coastal China felt the pinch from U.S. tariffs, with some factories reporting order declines and considering relocation to Southeast Asia. China’s overall economic growth decelerated to 6.1% in 2019 – the slowest in 29 years – partly due to falling exports. To counteract the downturn, Beijing rolled out stimulus measures: tax cuts for businesses, ramped-up infrastructure spending, and looser credit via local government financing (reflected in a jump in “total social financing,” a broad credit measure). These steps cushioned the domestic economy, preventing a harder landing. Indeed, by late 2019 there were signs China’s slump was bottoming out as manufacturing and retail data improved and the Phase One deal restored some confidence.

Politically, the trade confrontation strengthened hardliners in Beijing who advocate for greater self-reliance. China doubled down on its Made in China 2025 initiative to develop indigenous high-tech industries – from semiconductors to electric vehicles – so it would be less vulnerable to U.S. export bans. The temporary cutoff of Huawei from U.S. chip suppliers in 2019 served as a wake-up call. Similarly, Chinese authorities took steps to fortify the financial system: slowing down capital outflows, managing the yuan’s exchange rate to avoid destabilizing devaluation, and even quietly trimming holdings of U.S. Treasury bonds (though fears of a mass sell-off of U.S. debt did not materialize, as China recognized such a move could backfire on its own economy).

For the United States, one ironic outcome of the tariff battles was that the trade deficit with China barely improved – American imports from China did drop, but imports from other countries rose, and China’s retaliations made U.S. exports more expensive. By 2019, the U.S. trade deficit in goods with China was roughly back to 2016 levels, and global supply chains had begun a slow reorientation rather than outright reshoring. Some U.S. companies did pivot sourcing to countries like Vietnam, Mexico, and India to avoid tariffs, a trend that could have long-term ramifications for China’s role as “factory of the world.”

Crucially, the standoff highlighted underlying economic vulnerabilities: U.S. fiscal health and Chinese debt. The U.S. entered this period with a rising budget deficit, worsened by tax cuts and spending increases. Bridgewater’s Ray Dalio has warned that America’s debt supply is growing far faster than demand. “The world is not going to want to buy” the scale of U.S. debt being issued, Dalio cautioned. He drew parallels to 1930s dynamics – noting that back then, debt crises and tariff wars fed off each other, leading to “shocking developments”. His concern: swelling deficits and aggressive trade policies could undermine the dollar and U.S. financial stability over time. China, for its part, grappled with a domestic debt bubble of its own (especially in real estate and local governments). The trade war made it harder for China to simply export its way out of trouble, forcing reforms and uncomfortable adjustments. Both nations, in effect, have had to confront economic imbalances revealed or exacerbated by their trade and investment tussles.

Despite these challenges, opportunities have emerged. In the U.S., sectors not directly hit by tariffs – notably technology and services – continued to thrive, benefiting from tax relief and strong consumer spending (aided by low unemployment and, later, low interest rates). The U.S. stock market march upward, led by tech giants, made American equities even more attractive relative to the rest of the world. That created a feedback loop of capital inflows strengthening the dollar and U.S. asset prices, even as manufacturing lagged. For China, the adversity accelerated strategies to climb the value chain. Chinese firms in industries from solar panels to 5G network gear captured bigger global market shares when U.S. firms became more cautious. Moreover, the Chinese consumer market – now the world’s second-largest – became a critical refuge for companies: global brands from Tesla to Nike leaned into China’s growing middle class to offset trade-related losses elsewhere.

In summary, the political and economic impacts of the U.S.-China decoupling have been complex. Each side absorbed some pain yet uncovered areas of strength. The U.S. proved its economy’s dynamism with record financial markets but exposed its reliance on debt-fueled growth. China showcased its industrial resilience and the power of its domestic market, even as export-driven growth slowed markedly. These shifts set the stage for a new global economic landscape in which power is more diffuse and the old playbook of globalization is being rewritten.

Future Outlook: Diverging Paths and a New Global Order

Looking ahead, both risks and opportunities abound as the U.S. and China adjust to a more fragmented relationship. Many analysts believe we are entering a “bifurcated” global economy: one anchored by the U.S., and another increasingly influenced by China and its partners. The BRICS economies are expected to play a larger role in global growth. Collectively, the five BRICS now represent about 40% of the world’s population and over one-quarter of global GDP (nominal) – and over 37% in purchasing-power terms, surpassing the G7 share. In fact, by some measures 2023 marked the first time the BRICS output exceeded that of the G7. This momentum is forecast to continue. The IMF projects China alone will contribute roughly 22% of global GDP growth in the next five years, more than all G7 countries combined. India, another BRICS heavyweight, is not far behind with strong growth in the 6–7% range. Meanwhile, the G7 economies are slated for much slower average growth of about 1.7%. This growth differential suggests the economic center of gravity will keep shifting eastward and southward.

Expert projections underscore this trajectory. “History favors cycles,” notes Ruchir Sharma, pointing out that no country’s stock market leads forever. After a decade of U.S. outperformance, he expects capital could rotate toward emerging markets with better fundamentals. One catalyst might be valuations: by 2025, U.S. equities traded at far higher price-to-earnings multiples than many Chinese or Indian stocks. Should U.S. earnings falter or interest rates rise, global investors may rebalance portfolios, potentially igniting a “violent rotation” into under-owned markets abroad. On the flip side, if Chinese tech stocks and other emerging market equities continue to recover (helped by low starting valuations and improving local conditions), they could attract a new wave of international investment. David Tepper’s bullish stance on beaten-down Chinese internet companies could prove prescient if China manages to stimulate its economy and avoid major geopolitical flare-ups.

However, significant uncertainties cloud the future. U.S.-China relations remain a wild card. A collapse of the current trade truce or the imposition of new tariffs (for instance, on automobiles or more consumer electronics) would quickly sour market sentiment. Likewise, the technology cold war shows no sign of abating – export controls on advanced semiconductors, restrictions on data and apps (think TikTok or WeChat bans), and competing tech standards could force companies to choose sides. The U.S. is aggressively investing in its own chip production and limiting China’s access to cutting-edge tools, while China is pouring money into research to achieve chip self-sufficiency. The outcome of this race will shape the competitive balance in key industries like AI, quantum computing, and biotech for years to come. Notably, China has already made striking progress: it now leads in 57 of 64 critical technologies according to one global index, a leap from just a decade ago. This suggests China could narrow the innovation gap with the West sooner than many expect, boosting its economic prowess but also potentially provoking more pushback from the U.S.

Another area to watch is currency and finance. The BRICS nations have been quietly laying groundwork for financial cooperation that bypasses traditional Western-dominated systems. They founded the New Development Bank (a BRICS-led alternative to the World Bank) and have increased trade settlement in local currencies. Russia and China, for example, now conduct much of their bilateral trade in rubles and yuan, aiming to reduce dependence on the U.S. dollar. There is even talk of a future BRICS reserve currency or an expanded currency basket for trade – though such plans are in early stages. If successful, these efforts could gradually chip away at the U.S. dollar’s supremacy in global trade and reserves, which has thus far been largely unchallenged. For now, the dollar remains dominant, especially as rising U.S. interest rates in the early 2020s attracted capital inflows. But over a longer horizon, a multi-polar currency world could emerge, paralleling the multi-polar economic order.

From a political standpoint, both Washington and Beijing are calibrating their strategies for this new era. In the U.S., there is rare bipartisan consensus on getting tough with China on trade, security, and human rights issues. Future administrations (Democrat or Republican) are likely to maintain pressure, meaning tariffs or sanctions could remain leverage points. The U.S. is also strengthening alliances with other democratic nations to present a united front on setting trade rules and tech standards – for instance, the Quad alliance with Japan, India, and Australia or more coordination with the EU on regulating Chinese investments. China, meanwhile, is deepening ties with regional neighbors through initiatives like the Belt and Road infrastructure program and the RCEP trade agreement in Asia. It is also courting partners in Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East for energy and trade deals, partly to offset any loss of access to Western markets. The recent expansion of BRICS (inviting countries like Saudi Arabia, UAE, and others to join the bloc) demonstrates Beijing’s intent to build a broader coalition of emerging economies.

For investors and businesses, the future outlook will require navigating a less predictable landscape. Gone are the days when one could assume ever-increasing globalization would lift all boats. Now, strategy diversification is key. Many multinational companies will pursue a “China +1” approach – keeping a foothold in China’s vast market but developing alternate production hubs to hedge against geopolitics. Supply chains for electronics, apparel, and pharmaceuticals are already diversifying into places like Vietnam, India, and Mexico. This could be a boon for those economies, boosting jobs and investment – a trend to watch in the regional spotlight beyond just BRICS (e.g., Vietnam’s exports to the U.S. jumped amid the tariff war as firms rerouted orders).

Finally, one cannot ignore the role of macroeconomic cycles. The U.S., after years of expansion, could face a slowdown or recession in the coming years, especially if interest rates stay high to combat inflation. A U.S. downturn might narrow the performance gap with emerging markets, perhaps giving EM stocks and bonds a relative advantage for the first time in a long while. Conversely, China’s ability to return to its previous high growth rates is not guaranteed – structural issues like its aging population and heavy debt burden could cap growth near the current levels (~5% annually). Thus, the U.S. and Chinese economic trajectories might actually converge toward more moderate growth, even as their competition intensifies. Such a scenario would test which system can more efficiently allocate resources and innovate in the face of constraints.

In summary, the global economic outlook is one of cautious recalibration. The U.S. and China are charting diverging paths in some respects, yet remain interlinked. The coming years will likely see continued competition, periodic attempts at negotiation, and a search by the rest of the world to find balance – sometimes aligning with one side, sometimes hedging between both. Investors will need to be nimble, governments will need to be foresighted, and companies will need to be adaptable to thrive in this new paradigm.

What’s Next?

In the immediate future, a few key developments could shape the next chapter of the U.S.-China economic saga. Trade negotiations bear watching – if talks for a potential “Phase Two” deal resume, or if either side ramps up tariffs again, markets will react swiftly. Upcoming election cycles in the U.S. could also influence policy tone: a change in leadership might bring a different tactic (if not a different stance) toward Beijing. On China’s side, any major policy announcements from President Xi (such as economic reforms or stimulus measures) at party congresses or BRICS summits can signal the direction China plans to take amid external pressures.

Investors should keep an eye on corporate earnings and supply chain signals as well. Will American firms further reduce China exposure in their production and sourcing? How will Chinese companies navigate U.S. export controls – perhaps by developing indigenous substitutes or shifting to friendlier markets? Early signs of companies successfully decoupling (or struggling to do so) will be telling. Additionally, global forums like the G20 or APEC might become arenas for at least partial reconciliation or rule-setting to manage the competition.

On the horizon, new growth frontiers and alliances may emerge as by-products of this rivalry. For instance, we might see accelerated growth in Southeast Asia or India as they absorb investment redirected from China. Africa and Latin America could see heightened courtship by both the U.S. and China, each offering trade and investment deals to win influence. Technological developments will also be crucial: breakthroughs in areas like energy, biotechnology, or AI could tip the economic balance. If China’s bet on large-scale AI (fueled by vast data and a protected market) pays off, it could gain an edge; if the U.S. and allies maintain a lead in foundational technologies (chips, software, aerospace), they may retain their competitive advantage.

In essence, what’s next is a world marked by both heightened rivalry and the necessity for coexistence. Global challenges such as climate change, pandemics, and financial stability will require some degree of U.S.-China cooperation even amid competition. A possible scenario is one of “competitive collaboration,” where the two powers compete economically and technologically but collaborate when mutual interests demand it (for example, coordinating on macroeconomic stimulus in a crisis or jointly mediating regional conflicts that threaten stability).

For markets, volatility is likely to remain a companion. Yet within volatility lies opportunity. As Ray Dalio often suggests, a diversified approach – balancing U.S. and international assets, and hedging against extreme outcomes – may be the prudent path for investors navigating these cross-currents. Both the American and Chinese economies have proven their resilience over decades; betting on either entirely would ignore the strengths each brings. The more compelling story might be how the rest of the world, including the BRICS and beyond, leverage this moment to find growth avenues of their own.

In conclusion, the shifts in U.S.-China investment trends and the impacts of policies like tariffs are fundamentally reordering the global economic landscape. We are witnessing history in the making – a gradual transition toward a more multipolar world economy with new centers of influence. The journey will involve uncertainty, but also innovation and adaptation. As the dust settles on this period of change, a new equilibrium will form, and with it, new opportunities for those astute enough to recognize the emerging patterns. The narrative of Chinese tech stocks soaring or stumbling, of Trump tariff impact reverberating from Iowa to Guangzhou, and of BRICS economies converging to challenge old hierarchies, will continue to evolve. Staying informed with factual analysis and multiple perspectives is essential. After all, in a world where politics and economics intersect more than ever, today’s developments are setting the stage for tomorrow’s reality.